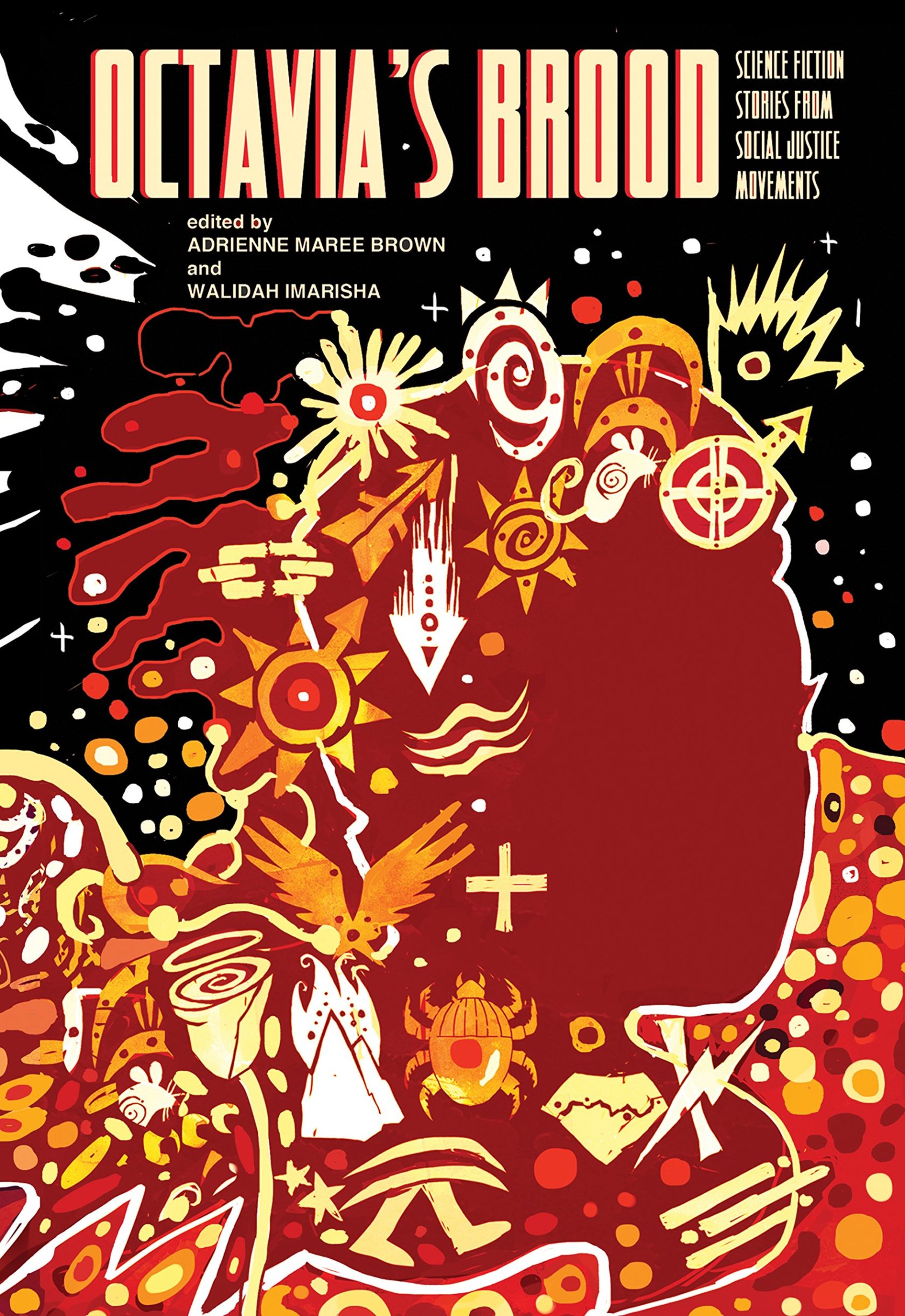

As societies around the world dip their toes in authoritarianism, we’d like to elevate authors of speculative fiction who imagine alternatives or help us demand the impossible futures of our dreams. In the Resistance Writers interview series, we’ll hear from a handful of writers from the 2015 anthology, Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. Each writer elaborates on sources of inspiration and how activism informs their work. Our hope is to provide a source of guidance for aspiring writers of visionary fiction.

Thomas Chisholm (TC)

How did you get involved with the Octavia’s Brood project? How did the editors, Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, discover your work?

Kalamu ya Salaam (KS)

I don’t remember the specifics but I was invited to participate. I’m not sure how the editors found out about my work in general. “Manhunters” is previously unpublished.

TC

What was your inspiration for “Manhunters?” Was it a piece you were already developing or did it come about once you were asked to participate in the Octavia’s Brood anthology?

KS

Feminism has long been one of my major areas of interest. “Manhunters” is from a major fiction work that was written years ago but which I never completed.

TC

What kind of impact have you seen Octavia’s Brood make since its publication in 2015? What role do you think politically motivated fiction can play in today’s climate?

KS

From time to time I see references to Octavia’s Brood. My impression is that the book is generally acknowledged as one of the major early works of the “afro-futurism” movement.

All fiction is politically motivated in the sense that the author is either re-writing or re-interpreting history or contemporary conditions, or the writer is projecting a “what-if” view of the future. Every piece of fiction either supports or challenges the past, the present, or attempts to predict the future. In most cases the writer, either consciously or unconsciously, is attempting to grapple with, understand, or critique what once existed, currently exists, or could possibly come into existence.

Video is the dominant form of written expression (smart phones, computers, television) and in combination with the widespread use of digital technology, literacy is near universal within our country in the 21st century. The combined forces of technically accessible video and the universality of literacy means that the majority of our thoughts and aspirations are informed or influenced by fiction, i.e. interpretations rather than strict representations of material and social reality. Moreover, the culture we live within is consumed as an afterthought rather than in the moment of its creation. In 99% of the cases, no one reads the work while it is being written but rather years and sometimes decades after it was composed.

There are only three possibilities: 1. Maintain what exists. 2. Bring back or re-create what previously existed. 3. Bring something new into existence. Most modern “writers” are trying to create something new, create work that previously did not exist. Just by being something new, work is most often a critique of the present or past rather than an extension of the present or past. Indeed, the very label fiction, implies that which is not the current reality, that which does not or did not exist. However, in order to create something truly new we must be deeply familiar with both the past and the present. The “truly new” is something beyond what is merely new to the author but rather is something that is new to both the artist and the audience.

Indeed, the very definition of being “modern” is to be new within the context of what is. So-called “politically motivated” artwork is artwork that consciously aims not only to be new (i.e. novel) but also insists on either critiquing or promoting the past, present, and future. Fiction generally is therefore subversive in that rather than focus on and/or encourage acceptance of what is, fiction projects and encourages what isn’t. To the degree that fiction advocates something that is beyond the control of the dominant forces of society, to that same degree such fiction is dangerous.

TC

In the current climate the United States is in, I see a lot of people (myself included) criticizing the powers that be, while taking little action. How did you find your voice, and your place within activist circles/movements? How have those experiences shaped your writing? What guidance might you give to aspiring artists/activists?

KS

I found my voice as a writer under the tutelage of middle school teachers who introduced me to black literature and fostered my interest in reading. In the late fifties when I grew up, I was not interested in racialized literature. While in school I read books about the life cycles of animals such as wolves and badgers. After being introduced to Langston Hughes, I read the writers he introduced to me, which means that I read all of the writers of the so-called Harlem Renaissance, writers whom I now identify as part of the Marcus Garvey era. This included Caribbean and African writers because Hughes produced anthologies that literally led me to Africa and all around the world.

I was active in both the civil rights and the black power movements. I never thought of my writing as separate from my social concerns, nor did I think of art as distinct from activism. Black music shaped my writing. I wanted to create work that was as forceful and as relevant as was our music.

My advice is know yourself, study the world. Knowing the self requires us to be deeply self-critical. Studying the world requires us to travel, to move beyond the familiar and to become comfortable with what is different from where and how we were born and grew up.

TC

What kinds of fiction or what particular authors have shaped your thinking? When writing fiction, what comes first: the concepts and ideals you want to explore, or the characters? Do you write with a political goal in mind?

KS

I do not and have not read much fiction. Early on in the sixties, my dominant influence in fiction was A Wreath For Udomo by Peter Abrahams. In terms of a body of work, I’ve read and enjoyed Milan Kundera.

Most of my work is concept/ideal driven. However, my major piece of fiction is “Walking Blues, A Meditation On The Life And Legend Of Robert Johnson.” “Walking Blues” is unpublished but excerpts have been published in anthologies and literary magazines.

Sometimes I feel like a nut, sometimes I don’t. Generally, I do not have a specific political starting point or goal. However, I have done work for specific purposes including writing advertising and publicity assignments.

TC

Throughout your life you’ve done a lot of work educating young people. What’s something they have taught you?

KS

Working with young people has helped me to keep my work accessible to my contemporary audience.

TC

What are you currently working on, politically and/or creatively?

KS

I am mainly organizing my work from over the years in a variety of genres: poetry, fiction, essays, drama, and screenplays. My latest non-fiction book is Be About Beauty, which includes a recent essay focusing on care-giving.

Originally published at FrictionLit

Also available on Medium